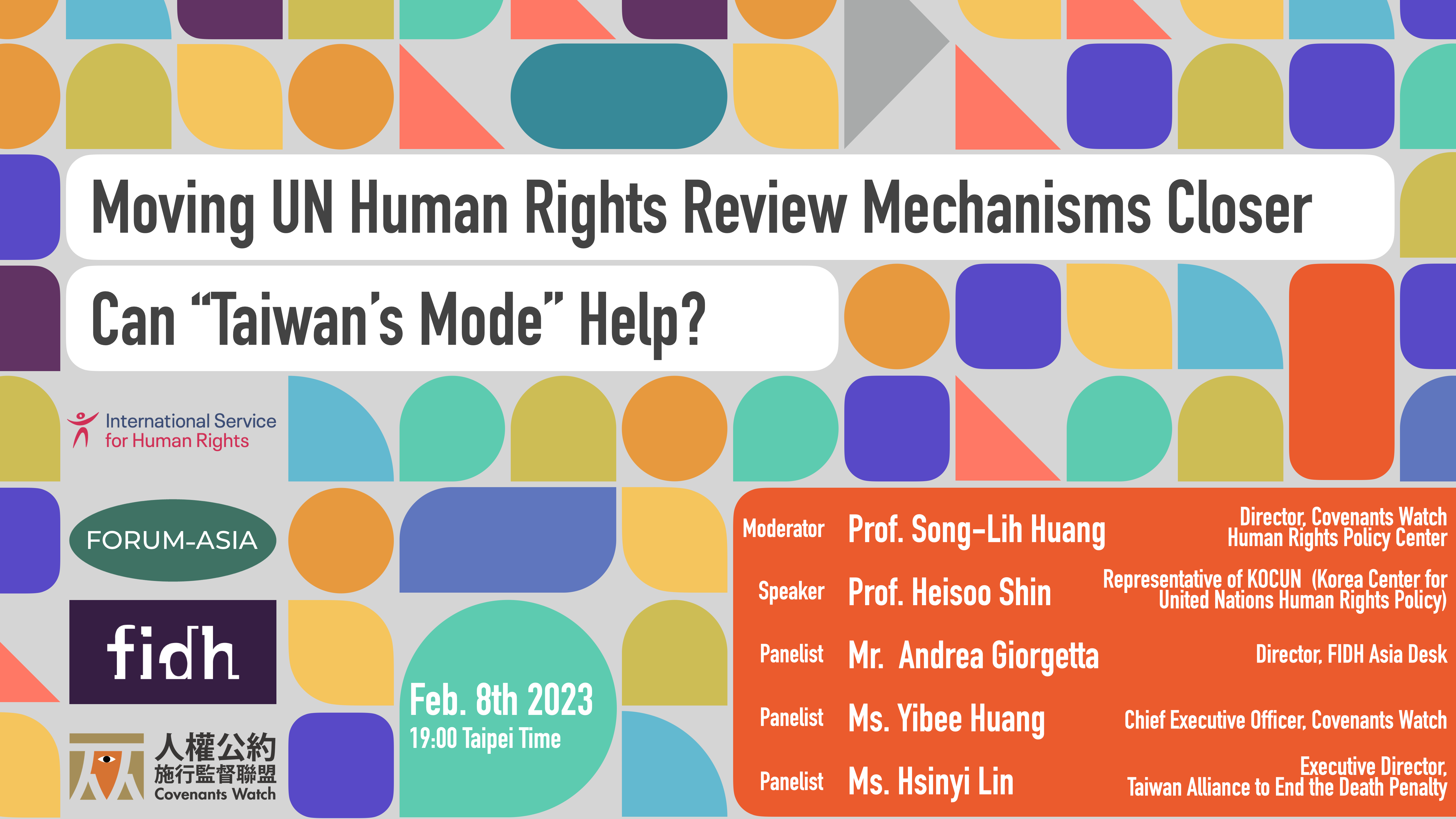

Online Forum|Moving UN Human Rights Review Mechanisms Closer: Can “Taiwan’s Mode” Help?

Global crises in the past two years have posed great challenges to human rights. Amidst the chaotic surroundings, Taiwan has demonstrated to the world not only its resilience but commitment to uphold the freedom and dignity of its people. Political constraints have not detracted from the island’s determination to stand by universal human rights standards. As of January 2023, 6 core UN human rights treaties are of legal effect in Taiwan.[1] More significantly, exclusion from the UN system has prompted Taiwan to “transplant” the international review mechanism onto the island, tweaking it into a unique “Taiwan’s Mode” of review. So far, this local mechanism has contributed to the establishment of Taiwan’s National Human Rights Committee in 2020 and the enactment of National Action Plans in 2022. Assuming the 4 Concluding Observations received from last year’s reviews are to be taken seriously, further advancement might be expected, albeit with an admitted dose of optimism.

Given the uniqueness of Taiwan’s review mechanism, it is worth asking what relative strengths and weaknesses such model possesses when compared to the current UN mechanism. After all, “[n]orms are not intended to be drafted for their own sake.”[2] Looking at the international human rights landscape, there seems to be “a serious rift between standard-setting and implementation.”[3] Indeed, the UN report-centric review system has been described as “less of a dialogue than a disjointed discourse.”[4] While attempts have been made to alleviate the problem, great room for improvement persists. Among suggestions made, often we see calls for an enhanced follow-up mechanism and further engagement of the local civil society.[5] In terms of follow-up, can Taiwan’s “Responding Action Plan” be something of value to learn from? Has the high level of civil society participation embodied rights “vernacularization”[6] in Taiwan? Is this the key to driving actual changes on the ground?

On the other hand, human rights in Taiwan do not exist in a vacuum. Without the media exposure such international event as UPR attracts and the external peer pressure, how do we ensure there is an equal amount of official commitment to those “unpopular” recommendations as those “lower-hanging fruits”? What problem might there be when the one who holds the review is the one to be reviewed? Whether, and to what extent, is the Taiwan’s mode of review an advanced form of ritualism, whereby “the process of continuous improvement itself [becomes] ritualized,” allowing some to bask in the radiance of human rights without embracing its value?

As Crawford and Alston put it at the turn of century over 20 years ago, “in human rights terms the twentieth century yielded a valuable legacy of internationally agreed standards and the creation of a set of institutional arrangements designed to monitor compliance with those standards. But the overriding challenge for the future is to develop the effectiveness of those monitoring systems.”[7] Apparently, no monitoring system can provide an ironclad guarantee of constant betterment of our world nor eliminates the possibility of blatant, atrocious abuse. Witnessing the great sufferings of the many, we are reminded time and again of the inadequacies of our current mechanisms. However, the way forward lies not in “despair and abandonment,” but in “courage, flexibility and imagination“ as well as “healthy self-criticism, appropriate candor and realistic scepticism.”[8]

With that in mind, Covenants Watch is honored to have Professor Heisoo Shin, who is the Representative of Korea Center for United Nations Human Rights Policy (aka KOCUN) and has sat in the Review Committee for all 3 rounds of Taiwan’s CEDAW Review, to speak to us on her experience with Taiwan’s review mechanism, its relative strengths and weaknesses compared to the UN mechanism, as well as the lessons they might draw from each other. For an NGO’s perspective, we have Mr. Andrea Giogetta (Director of FIDH Asia Desk), Ms. Yibee Huang (Chief Executive Officer of Covenants Watch), and Ms. Hsinyi Lin (Executive Director of Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty) to share with us their side of the story. The event will be hosted by Professor Song-lih Huang, Director of Covenants Watch Human Rights Policy Center. No discourse on human rights can flourish without diverse participation and open conversations. So, whichever field and wherever you are from, we cordially invite you to join us for a fruitful discussion. Hope to see you online!

|

Footnote:

[1] Except ICERD, which Taiwan ratified whilst still a UN member, all 5 other treaties (ICCPR, ICESCR, CEDAW, CRC, and CRPD) have been incorporated through enactment of parallel domestic legislation.

[2] Anne F. Bayefsky, The UN Human Rights Treaties: Facing the Implementation Crisis, 15 Windsor YB Access Just 189 (1996).

[3] Id.

[4] Rhona KM Smith, International human rights law 170 (8 ed. 2018).

[5]Id. at 177; Manfred Nowak, The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights: A link between decisions of expert monitoring bodies and enforcement by political bodies, in The UN Human Rights Treaty System in the 21 Century 251 (2000).

[6] Hilary Charlesworth, Swimming to Cambodia Justice and Ritual in Human Rights after Conflict, 29 Aust YBIL 1 (2010).

[7] Philip Alston & James Crawford, The future of UN human rights treaty monitoring (2000).

[8] Michael Kirby, United Nations Special Procedures: A Response to Professor Hilary Charlesworth, 29 Aust YBIL 17 (2010).